This post is going to be a bit different. Instead of providing a forecast or sharing a storm chase, it will be a reflection and commentary on how we can prevent future weather-related incidents from occurring in the wake of a deadly concert stage collapse at the Indiana State Fair on Saturday night. With the Minnesota State Fair beginning in a couple weeks and the severe thunderstorm season ongoing across the Midwest, I felt this would be an appropriate time to reflect on the tragedy in Indiana, and understand what proactive measures can be taken to prevent similar incidents from occurring in the future.

The collapse was caused by high winds that moved into the fairgrounds from severe thunderstorms in the vicinity. As the winds reached the grandstand area where the stage was located, it is believed the winds were as high as 70 MPH. Here is video of the collapse as onlookers awaited for the arrival of the country singing group, Sugarland. Five people are known dead, and 45 were injured.

The storms were sparked by a cold front moving through the area during the evening hours on Saturday. Just before 6 PM local time, a severe thunderstorm watch was issued until early Sunday morning for central Indiana as a line of storms formed in Illinois and moved eastward.

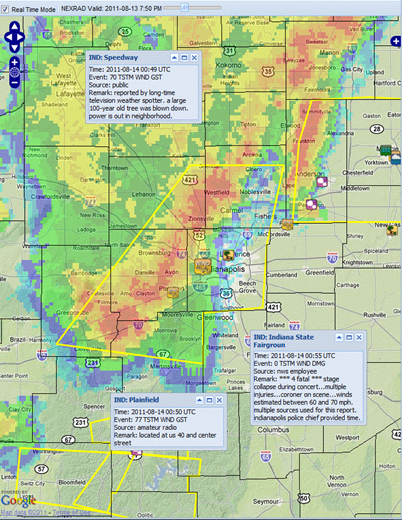

As the storms continued east into central Indiana, a Severe Thunderstorm Warning was issued for Marion County, and the Indianapolis area at 8:39 PM local time. The stage would collapse 10 minutes later, at 8:49 PM. Here is a radar loop of the storms moving into the Indianapolis area:

Damaging wind gusts were reported (actual ground truth) with the line of severe thunderstorms near Indianapolis. Winds of 70 MPH were recorded, just west of Indianapolis, at Speedway in Marion County, and 77 MPH at Plainfield in Hendricks County, west-southwest of Indianapolis. By rule, any winds over 70 MPH are considered destructive, and the National Weather Service usually goes with this wording in warnings where winds may reach this threshold. Just to compare straight-line winds to other natural hazards, hurricane-force winds are classified as 74 miles per hour or greater, and EF-0 tornadoes have winds between 65–85 MPH. Here is what radar looked like at 8:50 local time, one minute after initial reports of the concert stage collapsing. The strongest winds were just out in front of the leading edge of the thunderstorms that extends several miles - an outflow boundary, or “gust front”. I believe this is the aspect of the storm that caught the public off-guard.

According to Indiana State Police, State Fair personnel were in contact with the National Weather Service throughout the day for weather updates. In reviewing this timeline, communication between the fairgrounds and the local weather service appeared to be adequate as there was an awareness level that severe weather was possible during the day. This was followed up with additional updates of severe thunderstorm watches/warnings in effect for the area. There was advanced warning provided by the National Weather Service in Indianapolis. In fact, I thought the local weather service handled this night pretty well overall. Where the fault lies, in my opinion, is how the weather information was conveyed from State Fair officials to the general public. An announcement was made to concert attendees by Fair officials at 8:45, six minutes after the warning was issued, of severe weather present and where and when to seek shelter. Why was there such a delay in relaying this information? In the world of weather, six minutes is a long time, considering how quickly thunderstorms can move. In addition, according to The Indianapolis Star, officials did not officially call off the concert, thus thousands of anxious concert go-ers decided against heeding the warning:

But the weather near the Indiana State Fairgrounds was starting to get dicey. Backstage, State Police special operations commander Brad Weaver was watching an ugly storm moving in on radar via his smartphone. He and fair Executive Director Cindy Hoye decided it was time to evacuate the crowd.

But a minute later, when WLHK program director Bob Richards addressed the crowd, the word was that the show would go on, and that the crowd should be prepared to find shelter if things changed. Some of the crowd sensed the danger and left without further word. But the majority remained.

The severity of the thunderstorms was not communicated to the public properly, thus created a confusion as to whether it was necessary to evacuate since Fair officials determined the weather would not be turbulent enough to cancel a concert. Another issue I have is that State Fair operations likely had no idea of the actual wind reports received with this storm since they are not meteorologists. If they had tracked storm reports and knew winds in excess of 70 MPH were happening with this line of storms, I think their thought process would have changed a bit. Weather at the Fair was being monitored by a radar on a cell phone. Usually this kind of radar information available to cell phone users is basic, and doesn’t provide grand detail of what’s really going on. It can only tell you so much to an untrained eye, such as where storms are, but to a meteorologist, or someone experienced in the weather field, can interpret particular characteristics on radar. For example, the “wave” radar return ahead of a thunderstorm, indicating gusty winds with the outflow boundary. Meteorologists can tell you if a storm is rotating, or how fast winds may be moving looking at radar velocities. This radar loop assembled by AccuWeather details velocity winds heading into the fairgrounds at around 30 meters per second, or 67 MPH. If that’s enough wind to take down 100-year old trees, it can sure take down a temporary stage that acts like a wind trap.

There has been a growing trend of concerts operating during bad weather. It feels like the inevitable was going to happen sooner or later as the probabilities would eventually catch up. Unfortunately, it happened to be the Indiana State Fair where luck ran out. On August 6th, a stage collapsed because of severe weather before a Flaming Lips performance in Oklahoma. During the same weekend, Lollapalooza in Chicago narrowly escaped bad weather as the Foo Fighters were set to perform. In July, a severe storm toppled a stage in Ottawa, Canada when classic rock band Cheap Trick was performing. Closer to home, severe weather nearly affected people gathered at Huber Park in Shakopee to watch a fireworks display on August 6th as part of the city’s Derby Days (my take on the situation posted at The WeatherDesk here).

This was no “fluke” incident that I have heard some meteorologists and elected public officials use. We need to stop putting lives in danger and focus on public safety during weather events. It should not take deaths for change to be made. During my career working in the corporate world, I have learned over the years from management that it’s always better to be proactive rather than reactive. A situation like this could have been avoided if practices and policies were changed for dealing with severe weather. Here are a couple of my recommendations:

- A severe thunderstorm warning that affects the event location should be enough to postpone an event until the weather has passed, regardless if there is ground verification of severe weather from spotter networks.

- An on-site meteorologist or a private/public meteorologist team should be monitoring conditions 24/7 during the duration of the event, and be in constant communication with event officials since weather can change at a moment’s notice. We need people trained in the field of weather to call the shots that understand and can interpret weather conditions. Hazardous weather alerts should be transmitted as they are received so individuals have the maximum amount of time to prepare for bad weather.

- For outdoor event attendees, make sure you have a means for receiving weather alerts (i.e. automated text messaging through services such as CellWarn). Ultimately, it’s up to each individual to look out for their own safety. If you are attending an outdoor event and receive notification of severe weather in the area from event personnel or through your own channel, you should assume the worst and seek shelter in a sturdy building. It’s better to be safe and live another day. It’s also important to be up-to-date on weather conditions before heading out the door, and have an expectation for what may happen later in the day. In our information age, there’s really no reason why someone should be unaware of the day’s weather forecast.

With the Minnesota State Fair coming up, I really hope we don’t come close to seeing a repeat of what happened in Indiana. Injuries and deaths from an incident like this at one event is one occurrence too many.

RS

Ryan:

ReplyDeleteGreat job as usual. One thing I thought about while reading this is the use of NOAA's weather radio feed that is available over the internet. With a severe thunder storm watch having been issued early in the day, why didn't those in power at the fairgrounds have the capability to feed the severe thunder storm warning from the local WFO over their public address system?

That's a great idea, Randy, and should be a technically plausable solution. I know around here that most radio stations will broadcast tornado warnings automatically over their frequency. It may be an FCC requirement however.

ReplyDelete